My Singapore Misadventure, 1979

In The Same Boat

#

In The

Same

Boat

Story and website design by Nam Nguyen ©2016

Photographs by Vincent Leduc ©1979

#

In April 1979, at only 12 years old, I survived a terrifying boat journey in the Gulf of Thailand. Our boat was repeatedly attacked by deadly pirates and endured a violent sea storm throughout the night. So why, just one month later, did I make what was considered by others to be a “crazy” decision, to leave the relative safety of my refugee camp in Indonesia (as well as my three cousins) and travel alone on a second boat journey to Singapore?

The man responsible for convincing me to runaway was a “Crazy American Cowboy" named Gary Ferguson, a Vietnam veteran from Phoenix, Arizona. Gary came to Buton to help the Vietnamese refugees. At the camp, everyone loved Gary, especially the young children and kids my age.

I still vividly remember the first time I saw Gary. He was the first American I had ever seen in my life. He was dressed like a cowboy, wearing a big hat and leather boots. The communist propaganda depicted the American soldiers, the Party’s former enemies, as giant hairy monsters who eat Vietnamese babies; however, what I saw in Gary was a big and gentle man with a warm smile. He was always surrounded by the Vietnamese children, and he constantly reached out and greeted everyone.

On the first day of his visit to Buton, Gary showed off his tape player and recording equipment. His tape player was a treasure for the refugees because there was no electricity at the camp and almost no one else had any type of electronic devices. Gary demonstrated to the crowd how the tape recorder could be used to record voices, play music, and more importantly, to practice English. Since the time our boat arrived at the island of Buton, I had been told by the adults to study English every day. They suggested it would help prepare me for migrating to and immersing myself into an adopted Western culture, but I had never put too much thought into it, until I saw Gary.

After Gary’s first visit, I made a plan that I would approach and speak to Gary in English the next time that he returned. With the help of a Vietnamese-English dictionary, I was able to compose three greeting lines. I rewrote the English sentences on a notebook a few dozen times to help me memorize the greeting. I spent the rest of the night practicing the pronunciation.

When I woke up the next morning, I was very tired from lack of sleep. The thought of meeting Gary suddenly made me very nervous. My neck muscles stiffened and my lips were shaking so uncontrollably that I was unable to utter the English words correctly. I tried hard to practice speaking the sentences in my head over and over, while telling myself to be brave, knowing that I had only one shot at impressing Gary that day.

The morning of Gary’s arrival, the camp was noisy and lively with festive flares circulating in the air. A large crowd of people had already formed at the base of the monkey bridge, which served as the camp’s pier, facing our hut above the water. Everyone was eager to see Gary on his second day of visiting the refugees. The refugees erupted with loud cheers the moment Gary emerged in the distance. As he stepped out from a small canoe docked against the skinny monkey bridge, I couldn’t help giggling as I watched Gary walking slowly with both hands holding tightly onto the rail. He was looking down at the water as if he was afraid of falling. The crowd went wild and the cheers got louder as Gary came closer. Everyone was eagerly watching his every move.

When Gary passed the section of the bridge adjacent to my hut, he paused for a moment and looked up with a big smile to acknowledge the crowd, which responded to him with even louder cheers. Gary reacted by letting go of the railing with one of his hands to wave to the crowd. As he raised his hand, his feet suddenly slipped and he immediately dropped down into the water. The impact created a giant splash along with a loud popping sound. For a moment, I couldn’t see Gary because he was submerged in the water. The water started to splash in all directions as Gary struggled to stand up. The whole time he was screaming, flailing around, turning and twisting in a circle.

There was commotion from the crowd the moment Gary fell, and then everyone became quiet, seemingly in a state of shock. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Gary no longer looked like a brave and stoic cowboy. His hat was floating in the water several feet away. Black sand covered his curly hair and dripped all over his face. He looked like a madman. Gary slammed the water repeatedly with both of his arms then he reached down to free his boots from the muck. He raised the boots above his head to empty the muck from inside.

Several men ran out to assist Gary in recovering his hat, which was drifting a few feet away in the waves. Gary stomped his feet against the ground angrily as he walked up to the crowd. Soaked with wet, black sand, he was screaming and yelling at the top of his lungs at everyone. A man translated to the crowd in Vietnamese: “He (Gary) is calling us ‘stupid for building such a dangerous and useless bridge’. He said ‘how could we walk in such a stupid monkey bridge?’”

I heard some laughter from the crowd. Some elders started speaking ill of Gary, calling him “A stupid American. A crazy cowboy.”

I wish Gary had known what he was getting himself into by losing his temper. As soon as he wiped off the mud and sand from his hat and boots, he looked up, raised both of his arms and pointed his index fingers at two men dangling at the top of two coconut trees. At the base of the trees, there were about a dozen fresh coconuts scattered on the ground. Gary headed to one of the trees and walked in circles around it to examine the coconuts.

He looked up screaming and yelling loudly at the men above. I couldn’t understand what Gary was saying, but he looked furious.

Gary may not have known it at the time, but the two men were up in the trees cutting down fresh coconuts to serve to him, as he was our special guest. A man translated Gary’s rant into Vietnamese:

“I am very disappointed to witness what happened today. I have tried hard to create goodwill with the owner of the island. You people came here uninvited. You took over their island. You already chopped all their (rubber) trees. And now you’re doing this? Cutting their coconuts, not one, two or three coconuts, but…. without their permission. How do you expect them to like you? To help you?”

The crowd was silent. Everyone avoided eye contact with Gary as he was speaking and pointing fingers randomly at people. Some elders walked away and some were shaking their heads in disbelief. I felt sorry for Gary. He was standing there all alone. It was quite a contrast to what we saw the day before. I wished I could comfort Gary and show off my English skills, but I was no longer in the mood.

It was several days before Gary came back to Buton. By this time, everyone was talking about a small fishing boat that had just arrived and was anchored several hundred yards from our camp. The women and children on the boat were not allowed to enter our camp. Local Indonesian authorities claimed that the island could not sustain the already overcrowded refugee population.

Everyone was busy donating canned foods, rice, fish and fresh water to the people on this boat, and I was delighted to learn that Gary had also stepped in to help. Despite numerous meetings with the local Indonesian government officials, Gary still could not change their minds. The authorities gave the newly arrived refugees two days to leave the island. In desperation, Gary crafted a plan to lead the people of the small fishing boat to Singapore, where the nearest U.S. Embassy Office was located.

That afternoon, Gary invited many of the island’s refugee inhabitants to join him on his expedition to Singapore. He even promised to help those who joined him attain the right to go to the United States. He asked them to meet at the boat before midnight. This prompt departure only left us with several hours to make our decision.

Even though Gary tried his best to explain to the refugees his travel plan and how his status as an American could enable him to persuade the Singapore authorities to accept the new boat people, most of the elders at Buton Camp didn’t take him seriously. I wondered if Gary’s recent outbursts had already damaged his reputation and lost some trust from the refugees. Some people thought he was insane. But I didn’t feel that way at all about Gary. In fact, what I saw in Gary was a person passionate about helping those in need and capable of accomplishing anything.

To my dismay, no one from the family I shared the hut with believed in Gary’s plan. In addition to their unwillingness to go on another boat ride with uncertain success, the others associated joining Gary with stupidity saying: "Don't be stupid and go with that Crazy American Cowboy!" Their warnings were of no avail, I had already made up my mind and went to sleep early.

Just after midnight, I snuck out of my hut while everyone was sleeping. Under the cover of pitch darkness, I made my way slowly and quietly through the cold and muddy beach water to board the boat and begin a new boat journey with Gary, my new found hero.

#

After getting on board, I was disappointed to learn that none of the other kids I knew in the camp came along. Other than Gary, I didn’t know anyone else on the boat. I suddenly felt very lonely and uncertain. I couldn't sleep.

I was shivering as the night breeze struck my face, arms, and legs. I could see Gary’s silhouette illuminated by the light of the moon against the dark horizon. I spent the rest of the night watching him talk with the men on the boat, hoping this would ease my worries.

#Gary

The next day, I was delighted to see the Singapore Harbor skyline appearing in the distance. A small plane came down from the sky and circled right above our boat several times before it flew away. Minutes later, a ship appeared on the horizon. What a powerful military machine! I couldn't help feeling anxious and thinking that all of us would be safely rescued. Everyone on our boat was cheering and waving their hands toward the oncoming vessel.

The mood quickly changed when the steel ship got closer. Soldiers on its deck pointed their machine guns and rifles directly at us while the ship was circling around our boat. I feared we were going to be shot. Everyone was panicking.

The soldiers eventually withdrew their guns. I believe it was because they saw Gary, who was shouting out loud in English, a language I hadn't yet understood.

After about fifteen minutes of exchanging information, I watched the Singaporean soldiers assist Gary onto their ship. What a relief. Everyone on my boat was quiet. We waited in hope for a miracle. Once again I felt relief and was glad that Gary was there to help us.

The waiting was hard. It must have been several hours before Gary finally emerged from the ship's cabin. He was calm as the soldiers were helping him get back onto our boat.

Gary explained we were not welcome in Singapore. The news was shocking to all of us waiting anxiously on the boat. He said he made many attempts to negotiate with the Singaporean government and the U.S. embassy officials, but he was unsuccessful. Our boat was not allowed to enter Singapore and we were required to leave.

The Singaporean soldiers wasted no time following their orders as giant ropes emerged from their ship onto our boat. An amplified voice ordered our men to secure the ropes tightly against the frame of our boat. Water poured from the back of the ship as it began to pull our tiny wooden boat away from the Singaporean coast. It was a very frightening experience. The waves behind the ship were so large and powerful that our boat was jerking and shaking violently. I worried our small boat full of people was going to capsize or break into pieces. After dragging our boat for about an hour toward the open ocean, the military vessel came to a stop and the soldiers ordered us to cut the ropes, then the ship sped away.

For the second time in my young life I found myself stranded in a boat with strangers. All the men, women, and children were quiet. No one said a word. We didn't know what to do or where to go. Everyone was in tears. I was devastated. I couldn't believe Gary had failed us. I was hoping for another option-- any option other than going back to Buton Camp.

The voyage back to Buton was dreadful. In the chill and darkness of the night, I had never felt more alone and invisible. I was lost and deeply hurt. There was no one I could talk to, nor was there anyone I could count on.

Staring out at the glossy black water moving along the boat, I contemplated jumping into the ocean. I tried to imagine what it would be like the moment my face, hands, and my whole body touched the water, I wondered if I would feel cold. I also envisioned myself diving deep down into the dark ocean. Then I thought about the possibility that I might change my mind and decide to swim back to the boat after jumping in, and considered how long it would take to catch it. I tried not to think of the big fish that I might encounter. I imagined closing my lips tightly and holding my breath for a long time, or opening my mouth and tasting the salty water. I asked myself, what if I regret the jump?

Suddenly, I was shivering uncontrollably. I became weak, tired and gradually lost interest in the idea. I tried not to think further by staring blankly at the moving water along the side of the boat for the rest of the night until I felt asleep.

…..

For the past 36 years, I’ve been busy with my new life in the United States, my adopted homeland. Occasionally I recall this unforgettable boat journey, and wonder about the chain of events that took place which led me to that painful circumstance. After all, I ran away from my cousins in Buton without hesitation. In my escape for freedom, I ran away from the very people who were supposed to protect and take care of me in my parents’ absence.

I’ve asked myself many times, why did I run away?

The story is long and complicated but the answer I have found is simple: I was a different kid. I was different than the other refugees and didn’t feel comfortable with the environment I was in. I was a lone North Vietnamese trying to hide my true identity while surrounded by South Vietnamese refugees. I probably felt unsettled subconsciously, and I was looking for a solution.

…..

In the early 1950s, my father left his home, first wife, and son, in South Vietnam to assist the Viet Minh guerrillas fight against the French for Vietnamese independence. After the French were defeated at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, Vietnam was divided into two countries: Democratic Republic of Vietnam (Soviet-backed Communist) in the North and Republic of Vietnam (United States-backed) in the South. This was the beginning of the long war against the United States. Trapped in the North, my father could no longer return to his family in the South. After 10 years of forced separation from his first wife and son, he met a Northern Vietnamese woman in Hanoi (my mother). They fell in love and started a family of their own, which eventually included my three brothers, a sister, and me.

A product of love, war, ideology, and geography, I was born and grew up during the midst of the War with the Americans in a town just outside of Hanoi, the Capital of Communist North Vietnam. In late April 1975, after the fall of Saigon and the end of the war, my father was finally able to travel back to Southern Vietnam to look for his long lost family, after having been stranded in the North for more than a quarter of a century. I accompanied my father on this memorable journey to Saigon. About a year later my mother was able to move with my brothers and sister to join us.

…..

After the fall of South Vietnam in 1975, many Southerners harbored a deep hatred towards the Northerners for their oppression, and for taking away their homes and businesses. Many wealthy families in the South were forced from their homes to live in new economic resettlements in the remote jungles. They were forced to abandon their livelihoods and work as farmers or construction laborers. Former Southern Vietnamese soldiers and officers (including my father’s first wife and their only son, my step brother) were taken to prisons or re-education camps to be tortured and and to perform debilitating daily labor. Many people refused to leave their homes and committed suicide. Families and relatives of South Vietnam’s government officials or military officers were put on North Vietnam’s communist blacklist. Many fearful families escaped on boats, risking their lives against dangerous sea storms and deadly pirate attacks. They eventually landed in refugee camps in neighboring countries such as the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia.

My cousins were born and raised in South Vietnam by a wealthy family. Their father, my father’s youngest brother, was a well-known and respected doctor in Saigon. Feeling fearful and uncertain of what might happen to his family, my uncle sent his children on a boat to escape the country’s turmoil in the hope they would find better and safer lives. My uncle also did a great favor to his older brother, my father, by paying the exorbitant fees, that could range from five to twelve bars of gold, for me to join his three children.

Leaving my family behind in Vietnam, I had to readjust my identity to blend in with my cousins and other Southern Vietnamese. I was technically a Northern Vietnamese. To protect myself from hostility, I tried not to speak freely with anyone so that no one would notice my heavy Northern accent. I didn’t want to be treated like an outsider, or in some cases, as the enemy. One of my cousins, who was bigger, stronger and several years older than me, always stared at me strangely, and often called me a “Viet Cong.” However, I felt relatively safe among the other refugees and the family that I shared a hut with at Buton.

…..

This is a personal account of one of the chapters of my life that I call “My 1979 Boat Journey From Vietnam,” a misadventure that I embarked on as a pre-teen. It was a formative experience that I documented years ago in school journals and occasionally told to loved ones. This story has lived in my heart for more than three decades. Until recently, the only images that existed were those that I created through my artwork, all based on the memory of these life changing events.

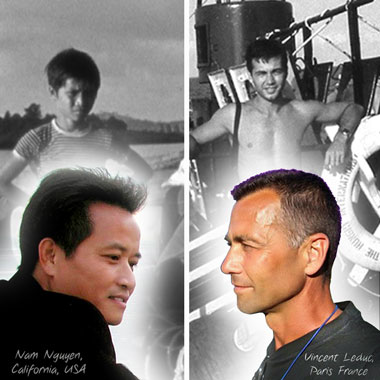

On September 23, 2013, I connected via Facebook with Vincent Leduc, a French photographer. I learned that during the time of my misadventure, Vincent was working as a photojournalist with Food for the Hungry International, a community service group offering relief to refugees. From this Facebook connection, Vincent shared with me his work and uploaded a series of photographs he took of the Vietnamese refugee experience. As I was browsing through all of the photos, images of a particular young boy with a look of despair on his face started to emerge. To my shock and disbelief, I suddenly realized that this boy was me . . .

#

#

These are Vincent Leduc’s original images of the people from this Singapore bound boat and me, as a young boy during this unforgettable journey more than 36 years ago. I am the boy wearing a dark brown striped T-shirt (marked with a ‘#’).

To discover these extraordinary photographs by Vincent, a man whom I had no recollection of seeing in the same boat as me, was a dream-like experience.

What a nice surprise and what a beautiful dream!

- Nam Nguyen, February 2016

#

The Runaway Teen: Having a hard time facing the reality of the misadventure, the journey back to the refugee camp was a dreadful experience.

The Photographer: Vincent Leduc on the Akuna ship in June 1979, during an operation to rescue the Vietnamese boat people in South China Sea, funded by Food for the Hungry International.

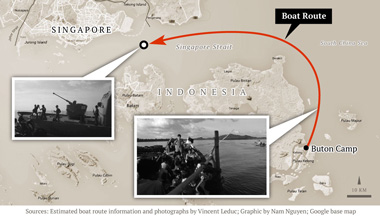

Where Our Paths CrossedMap shows the approximate route from Buton Refugee Camp in Indonesia to Singapore. Unbeknownst to us, this boat is where Vincent’s journey crossed paths with mine in May 1979.

CLICK ON MAP FOR HI-RESOLUTION

"We went on that boat for almost that night and the next day we were very closed to Singapore harbors. Many of the great ship were around us, some come out on board greeting, some staring and some ship even didn’t show us if there were any people on their ship. We though maybe they were afraid of our boat, a strange boat." "We chose to sail north in order to escape the risk of being spotted and arrested by the Indonesian authorities. We went north, then west to Singapore. On the way back we took the same road. The Singapore Navy was towing us toward the open sea, not heading Riau's Indonesia. We crossed the ship highway on the way back, the same way from where we came from. I recall it very precisely. Open sea, then the ship highway: container ships, oil ships, cargo ships, etc... in a line, following each other with a 3 or 4 miles gap, on their approach to Singapore (it was the fourth commercial port of the world at that time). We decided to paint a wooden board, about 1 by 1 meter with this words: SOS, VIETNAMESE REFUGEES (or boat people). Not any ships stopped, not any ship came to our rescue (confirming all the boat people accounts on this matter). And we came back to Pulau Buton from the north."

#

> READ MORE About Us

ABOUT

Nam Nguyen

I am a former boat refugee from Vietnam. Following a six-month stay at a refugee camp in Indonesia, I arrived in the U.S. in late November 1979. Eight years later, I became a naturalized U.S. citizen. I attended junior high and high school in Nebraska and graduated from University of Nebraska at Kearney in 1989. I’ve spent more than 21 years working at three major newspapers as a graphic journalist and director. I am currently working as a web designer and presentation specialist at an energy engineering and consulting firm located in Sacramento, California.

1975

Until the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, my father was stranded in North Vietnam, separated from his first wife, and their only son for more than 25 years. During that time, he met my mother and started another family. After the Fall of Saigon, my father was able to search for his long lost loved ones. Leaving behind my mother and my three brothers and sister in the North, my father took me on a remarkable 1700 km journey from Hanoi to Saigon. For days my father and I traveled over broken bridges, through bombed roads and cities, and through the countryside of North and Central regions that were littered with battered U.S. military equipment and artillery shells. We walked along with North Vietnamese soldiers and displaced civilians. We hopped between trucks, buses, river ferries, and cow wagons.

When my father finally located his family in the South, he learned that his first wife had become a nationalist, and their son, who was in his late 20s, was a policeman. They were both employed by the formerly U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government. His first wife, whom he hadn’t seen for more than 25 years, no longer accepted him nor wanted anything to do with him. My father was heartbroken. He left me in Saigon to live with my uncle, his youngest brother, a wealthy and respected doctor, while he traveled back to the North to retrieve my mother and my siblings. A year later we were all reunited in the South.

1979

Four years after the last Americans left Saigon (renamed Ho Chi Minh City), the city was in a deep economic crisis. The United States enforced economic embargoes against Vietnam after the end of the war which had taken a heavy toll on the country. The communist government was in full swing targeting the wealthy and the private business owners, taking away big homes and private businesses and using the name of Marxism–Leninism, the socialist ideology that suggested everyone is equal in terms of personal wealth and property. Wealthy citizens were disappearing without a trace, often taken away by soldiers in the middle of the night. Their homes and properties were repossessed by the government. Many home and business owners committed suicide in protest.

Border clashes with China in the North and Cambodia in the Southwest led to fear of another war. There was talk about thousands of people fleeing the country on boats each day. Some of my neighbors and classmates were disappearing randomly and never came back. I heard many terrible stories of people who died at the hands of the police. Those who fled in boats faced starvation, sea storms and pirate attacks as well as the capsizing of their vessels. Still, people were leaving in droves.

The thought of joining the exodus never crossed my mind because it was very expensive, costing approximately 5 to 12 bars of gold per person to escape Vietnam on these boats, and my family was poor. Then one afternoon in early April, my father surprised me with big news: he told me that I could join my cousins to escape my country on a boat. He wanted me to have a better life.

Joining almost a million other Vietnamese fleeing the communist state during the decade after the end of the Vietnam War, I was among 68 people tightly packed in the bottom compartment of a small wooden boat, headed to the Gulf of Thailand in mid April. Pirates attacked our boat repeatedly the second day of our journey. A violent storm came in the late evening just in time to chase the pirates away. The terrifying sea storms continued throughout the night and we were lucky to survive them.

The next morning, pirates continued pursuing our boat. Then a ship appeared from the horizon. About an hour later, all of us on the boat were safely rescued by the “Akuna”. We were on this vessel for about a week before its captain and crews helped us land in a remote island in Indonesia called Buton.

TODAY

Having lived in the United States most of my life, I love my new country dearly for the freedom and all the opportunities that I have had. I feel blessed having a loving family of my own - my wife and our four sons.

I am an artist at heart and I love technology and innovation. I enjoy working with the latest web design and 3D software at my current job. I hope someday to have the time to work on my passion for traditional art: drawing and watercolor painting.

IN RETROSPECT

Starting a new life in a new country with a different language and culture wasn’t easy. It was hard being a teenager without having the unconditional love and support from my parents. Living in the Midwest in the early 80s and being isolated from my family and the Vietnamese culture and community made me feel very homesick and lonely. My artwork helped me through the difficult times. But, those activities did not provide enough of a distraction to help me cope with the sadness and loneliness I felt. During my junior and high school years, I hopped between foster homes and was sometimes admitted to runaway teen shelters when a foster home was not available. These shelters were run very much like a jail – I was locked up, never allowed to leave and the only exposure to the outside was to pull weeds on the property in the heat of the day. I found solace and comfort by keeping myself busy with creating artwork. With my limited English vocabulary, I was not able to express my feelings. But drawing allowed me to release emotions and feelings in a way that other people could understand. It also provided a “bridge” to connect with them. My artwork provided a comfortable topic of conversation when, otherwise, no one would know what to say to the lone Vietnamese boy.

Spiritually speaking, I am still the same person I was the day I left my family and my home country of Vietnam 37 years ago. My heart still holds onto the young boy who was robbed of his innocence by time and circumstance. There is something missing, perhaps lost forever, that can never be recovered. To this day, I still find myself searching for that missing piece.

My immigration document from 1979 stated my birthplace as Saigon, South Vietnam, instead of North Vietnam’s capital city of Hanoi. It was due to my parents’ concern for my safety. I wished I didn’t have to lie about my place of birth to everyone -- my sponsor families from the Holy Cross Lutheran Church, teachers, classmates, friends, coworkers, bosses, neighbors and even my best friends whenever they asked about my family and hometown in Vietnam. It is something I still feel I need to hide in order to protect myself.

I still carry a slight Northern Vietnamese accent today. Living in an English-speaking world most of my life, I no longer think in my native language, but in English. However, my accent still exists and has led to numerous awkward moments with fellow Vietnamese living in the United States. Some turn their heads in my direction and look at me curiously. People often react with confused and skeptical expressions upon hearing I was born in Saigon. Short conversations often end quickly with an inquiry as to the specifics of my Vietnamese origins. I used to wonder if it was because of my lack of Vietnamese vocabulary, or perhaps that I’ve said something inappropriate. I eventually came to the conclusion that my Northern accent was recognizably different than the accent of the South Vietnamese, especially to family members of former U.S. backed South Vietnam military veterans. Many of these people were survivors of Communist Re-Education camps and had formed negative associations with the Northern accent. As a refugee, having this characteristic that I could not change or easily hide made me feel like an outsider and I wished more than ever to be reunited with my family in Vietnam. As an adult, I am still very aware of the assumptions other Vietnamese people make about me when they hear me speak.

I will never forget a special gathering with all of my cousins in Southern California during the late summer of 1989. We were enjoying a wonderful authentic Vietnamese dinner with lively discussion about Vietnamese foods. We were talking about the unique cooking styles and tastes of three regions in Vietnam: Northern, Central and Southern. We debated about which region excelled in the preparation of certain dishes. Then out of the blue, one of my cousins looked at me and asked, “Which region do you identify yourself with? Do you see yourself as a Northerner or Southerner?” I told everyone right away, “I feel that I am both, so I am just a Vietnamese.” Then the same cousin demanded: “You can only pick one, a Northerner or a Southerner?” Everyone was quiet. I paused for a moment and said, “Well, I was born and grew up in the North and I only lived in the South for four years, so I feel more like a Northerner.” My cousin continued, “So you say you are a Northerner?” I nervously reassured, “Yes, I am a Northerner.” The joyous atmosphere evaporated into thin air. The conversation was over. No one was talking as we ate the rest of the meal in silence. I felt hurt and guilty, thinking that I may have disappointed my cousins with my answer.

My cousins and I arrived in the United States from Buton Camp in late November of 1979. We lived together in our first American home, a rental house, in Kearney, Nebraska. The church that sponsored us provided the home, a part-time job for my oldest cousin, food and support. It was an exciting short period of our new life in America. I enjoyed learning English at school and attending church services on weekends, but things soon got rough between me and my cousin. This cousin was vengeful, never really accepting me because I was born in the North and he called me a Viet Cong. He was having a difficult time dealing with a leg wound he suffered in a house fire during the war. I believe due to the pain from not having the medication he needed, his personality became unpredictable and he sometimes turned violent against me.

The fights usually started the moment he saw me come home from school. As soon as our eyes met, the chase began. Books would fly everywhere as I used my backpack to shield myself against my cousin’s kicks and punches. Even when I locked myself in the bathroom for a bath, he kicked down the door and we would wrestle in the bathtub water while I was naked. I usually restrained myself from fighting back, waiting for an opportunity to break free from him so I could run away. On one particular occasion, it was in the middle of a freezing winter in Nebraska so I couldn’t run outside. My cousin chased me all over the house and we ended up wrestling in the living room. During this struggle, we locked each other’s necks to the floor for so long that we both became so tired, unable to move, and almost out of breath. We had many similar fights. One time I ran to our back yard in the dark and freezing snow while wearing only shorts and no socks or shoes, and hid behind a garbage bin for several hours. I also recall a time when I hid in the floor heating duct under the area rug of the family room after being chased by my cousin. I felt bad for my other cousins who were unable to break up our fights, and spent hours searching for me inside and outside of the house so frantically that night. I wanted to let them know where I was hiding, but was afraid the consequences. So, I just stayed calm and slept in that duct all night, not coming out until the next morning.

When all my cousins decided to move away from Kearney to bigger cities in Nebraska and California in the spring of 1980, I took the opportunity to stay behind in Kearney, alone, and began living with foster families. Since then, each of us has moved on with our own lives and become busy with our careers and families. We haven’t seen each other much over the past 37 years. To this day, whenever I think of my cousins, I feel there is a distance between us. It saddens me that our shared refugee experience didn’t bring us closer. We each had to deal with the separation from our home country and integration into our new country in our own individual ways. It was a very emotional and difficult time for us all. I don’t have any hard feelings toward them and I am forever grateful to their father, my uncle, for giving me the boat ticket to freedom and the opportunity for me to get where I am today.

As the years go by, I become more content living independently on my own. That is, without the family I left behind in Vietnam and the cousins I fled with. Of course, I still miss them but yearning for them and the culture I remembered, doesn’t have as strong a hold on me. I feel peaceful as an American citizen. The strange thing is I feel more free when I am surrounded by non-Vietnamese people and speaking in English. I had a great experience in college in Nebraska and I was blessed with a wonderful career at three major newspapers for more than 20 years. But life is full of unexpected incidents, and sometimes, in a split second, memories of my childhood living in Northern Vietnam flood back and catch me off guard.

I remember a long carpool ride 17 years ago on a California freeway to a meeting with my boss, a newspaper editor who was a Japanese-American and a Vietnam War Veteran. We talked about our backgrounds and our common struggles as Asian Americans against negative stereotypes. We were having such a wonderful time sharing our stories about the Japanese and Vietnamese foods and cultures in Sacramento area. Then he asked me what part of South Vietnam that I came from, to which I responded Saigon. He launched into a story about his time in the navy and the U.S. bombing raids over North Vietnam and its capital city, Hanoi, in 1972.

As a U.S. seaman on an aircraft carrier in the Gulf of Tonkin, he and the other navy officers worked non-stop for days and nights, loading weapons onto jet fighters. As he relayed his story, I remember my body became tense as I restrained myself from shaking. My hands were sweating as I listened to him described the details: the constant jet breaking sounds, the scorching heat atop the carrier’s deck, and all the rolling bombs and rockets. At this moment, I couldn’t help but recall the living conditions of my family during this non-stop bombing period. My family and all our neighbors had to hide inside a small, deep, wet, dark and muddy underground bunker just outside of Hanoi 24 hours a day, while the earth was shaking and vibrating constantly from the bomb explosions in the near distance. For many days, we couldn’t go to school. We couldn’t even cook our food because the fire and smoke would make our home a bomb target. It was a surreal experience hearing my boss proudly telling me about his service in Vietnam, while I was awash in memories of the consequences of those bombings.

Time has changed. Technology is changing faster than ever before. Vietnam as a country has changed dramatically, both economically and politically, during the past 30 years. Thanks to the power and speed of social media, people in Vietnam today are connected to all parts of the country and all over the world in real time. For the first time, many people have access to news and world events through their personal mobile devices instead of depending solely on the government-run media. Social media has become an important tool to help the people in Vietnam voice their concerns and protest against government corruption with news, photos, and video clips taken with smartphones, then shared instantly online. The Vietnamese can now freely travel all over the country and some travel overseas on jumbo jets to work, attend universities, or visit other countries including the U.S.

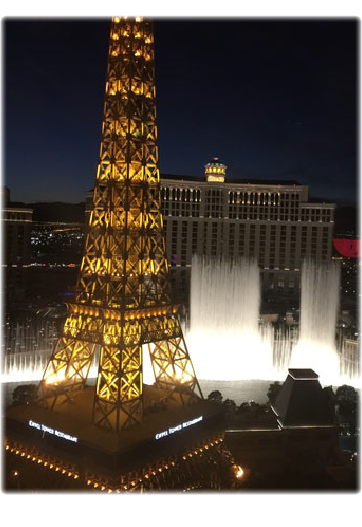

Just recently, my wife and I were at a casino in Las Vegas for a short getaway trip. We had a dinner at a very nice restaurant and happened to be seated next to a Vietnamese-American couple from San Jose, California. After the introductions, our conversation turned to laughter, champagne, and cheers. Our group happily talked and toasted drinks non-stop. We had so much fun sharing stories about foods and travel trips back to our home country, etc. The Vietnamese couple was telling us about their fast paced lifestyle: regularly dining at fancy restaurants, staying in nice hotels, and often taking air flights to parties with friends to visit fun destinations such as Las Vegas and Los Angeles. We shared our story too; that we have four kids, my wife and I drove many hours to Las Vegas from Sacramento, and that we slept in the back seat of our car for two nights to save time and money. It was such a fun experience chatting with fellow Vietnamese Americans our own age, with similar experiences. We were really enjoying each other’s company.

Suddenly, the Vietnamese man, who was sitting besides me, put his face close to my left ear, and spoke with a heavy Southern accent, “So, you have a Northern accent. You must be a Northerner heh?” I looked at his eyes and studied his facial expressions. He was a few years older than me. He had a funny, happy face, with a warm smile. I was about to give him the usual quick response but my wife, a Southerner and an Amerasian, stepped in right away on my behalf and said “His mother is from the North, his father is from the South.”

The Vietnamese man looked amused and curious as he responded, “I am a Northerner too, but I don’t speak with a Northern accent. My parents moved to the South in 1954. We are Catholic people.” (Note: After the French left Vietnam in 1954, the country was divided into two sides when the Viet Minh Government under Ho Chi Minh took control of the North. As a result, thousands of North Vietnamese Catholics fled southward out of fear that they would be persecuted by the Communists.)

Under the dimmed spotlight glowing on the man’s face, I could see his sparkling eyes staring at me without a blink, as he waited for me to tell my story about my family. So I did just that. I told him that I was born in Phuc Yen, just north of Hanoi. For the very first time, I told a stranger the name of my real hometown. I told him about my father and my mother, how they met, when I was born, and when I moved to Saigon, and when I escaped from Vietnam.

I held my breath for a moment as I waited for the man’s reaction. But he was calm, with a cool look as if he wanted me to tell him more. I felt a little uneasy as the heat from my blood spread rapidly throughout my body. Suddenly the Vietnamese man smiled and raised his champagne glass toward me for another toast. My wife and the man’s partner quickly joined in with their own glasses. Everyone cheered and then our conversation turned to shared stories about our unforgettable experience as boat people and refugees from more than three decades ago.

That evening, after returning to our hotel room, I sat alone for several hours enjoying the views through the window of our room on the 24th floor of the Paris Las Vegas Hotel. What a magnificent view of the Eiffel Tower (replica) and the spectacular water show in front of the Bellagio Casino. I felt peaceful and unusually relaxed. I felt the joy of a burden being released. The music wasn’t playing but my heart felt like dancing. I couldn’t stop smiling. Basking in this peaceful state, I took my time, before joining my wife for our usual evening stroll of the Las Vegas Strip. A special feeling still lingers in my soul. I felt extraordinarily powerful. I felt free. Just like a wonderful dream.

I dream that someday in the future, I can finally fold these chapters of my life into a book, or other form of communication. Deep inside, I felt the need to share my stories so that I can fully move forward.

Until then, a part of my heart is still in Vietnam.

. . . .

ABOUT

Vincent Leduc

To see the world as a university of life conducted me to travel a lot. Hitchhiking in France and Europe from the age of 15, as a seaman on cargo ships around the world at 19, as a hippie on the road to India at 20, then as a free-lance photographer in South East Asia, where I followed several main subjects: the communist take-over in Laos, the refugee from Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, the consequences of the conflict on Thailand, the Karen and Karenni guerrilla resistances in Burma.

During the last 30 years, I became cameraman, director and producer, founding a production house in Bangkok in 1988. Back to France ten years later, I worked as a travel documentary director for the « Behind the postcard » program which I created, directed and produced for the channel Voyage, then for the « Échappées Belles » program on France 5, for which I have directed numerous « Mythical routes » across the world.

1975

The fall of Saigon on April 30 had the effect of an alert signal on me. I learned the news a month later at the Alliance Française of Pondicherry in India through the newspapers that I came to consult after four month of hippie traveling from France. The Khmer Rouges had taken Phnom Penh on April 17. Only Laos was still reachable. On the road, this country was referred to as the opium paradise, but for me it woke up a powerful feeling for Indochina taking roots from my childhood. It took me about one month to reach it, on June 25, the day after the last Americans were expelled from the country by the communist forces. Far from the horror of the Vietnam war and the atrocities of the Khmer Rouges in Cambodia, the Pathet Lao seized quietly the power in a six-month period during which I had the time to fall in love with the country and decide to live there. Passionate witness of this take over events, I started to take photos on the field, after being officially recognized as a professional photographer by the new authorities thanks to a fake press pass. But two months after the Popular Democratic Republic of Laos proclamation (Dec. 2) I was expelled as most citizens of non-communist countries.

1979

The following four years, I covered the situation of the refugees from Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, from Thailand, with numerous trips to Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. Having just the Mekong river to cross, Laotian and Hmong (mountain people) refugees were the first to arrive, soon reaching by the hundreds of thousand, and were packed into camps all along the border. It took a much longer time for the Khmer to reach such a number. Survivors were arriving sparingly, haggard, terrified, hungry, sick, wounded. Their stories were telling of a state of atrocity we had never known since the discovery of the Nazi concentration camps at the end of World War 2. Bear witness then took another dimension for me.

I started to sell my photos to the international news agency desks, AFP, UPI, AP, in Bangkok. But soon a major problem appeared. There was no demand of news concerning refugees nor any interest for the post-Vietnam war situation. United States were grooming the wound of their first defeat and French as well as American intellectuals, who had supported the communist victory, preferred to keep their eyes, ears and mouth shut. Facing the terrible human drama amplifying rapidly under my own eyes, this incredible and unjust situation committed me to a vocation of observer and witness. These four years were those of silence on the Cambodian genocide taking place in a country turned into a gigantic concentration camp, also silence on the misery of the boat people of whom the precise number were never known. It has been estimated up to 800,000 Vietnamese who succeeded to reach at a cost, with the frightening number of one over two, one who lost his life for one who succeeded.

After three years of this hell, the world suddenly woke up in late 1978 and mostly in mid 1979 when the countries of first temporary asylum in the region threatened to expel all refugees, precisely to alert the world public opinions. It is then, that international medias started to play drum, and launched large mobilization, that people of good will appeared. And Gary landed one morning in Bangkok. I meet him the very evening in a Patpong bar, the famous city red light district. He was drinking a beer next to me at the counter. In an unknown region to him, he needed a guide to go and see the various Food for the Hungry programs, including rescue with the Akuna ship in the South China Sea. It was for me the occasion to bear witness even closer to the boat people.

TODAY

All along my life in the field of picture, I experienced an uncertain equilibrium between the commitment to bear witness, critically, with in depth analysis, and the necessity of works providing a living such as company profile videos, television programs and even commercials. The question of ethics has always been and will always be central to me. At the ultra-liberalism era where everything is allowed, my last experience with this travel program on France 5, drove me to break.

Flirting with writing, pottery and philosophy, I am now living in my garden that I cultivate in a natural way, uniting works of earth, spiritual life, artistic creation and therapeutic curing.

IN RETROSPECT

I was writing a book about my first years of experience as free-lance photographer in South East Asia when I made this search on the Akuna and went across Nam. Among our exchanges one day, he wrote:

« Looking back, I learned that Vincent and I have traveled a very similar time table, and both of our lives have been profoundly affected by the Vietnamese boat people crisis and related events following the end of the Vietnam War. »

Similar calendar?

This affirmation seemed a bit strange to me. Later, I heard he echo. The echo of all those who new me and along my life reacted to my Asian experiences saying: « Ah, you followed the path of your father! » To which I always answered « no » in order to affirm my independence as well as to claim my own choices. The link of all that? Vietnam.

It is a long story.

My father was a film director, graduated from Idhec, the renowned Institute of high cinematographic studies. In 1955, less than a year after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu ending more than a century of French colony, the new South Vietnamese government, Francophile, placed an ad at the prestigious Idhec. It was looking for a director to create a South-Vietnamese cinematography within the cultural and information ministry. My father left with a one year contract the very year of my birth.

He directed his first Vietnamese films in the turmoil of events of that time, especially « North Wind, South Wind », a film shot in 35mm on the exodus of the catholic refugees from North Vietnam, and « Xuan, the Little Buffalo Keeper », telling the story of a peasant boy dreaming to navigate.

The contract broke up before end by the institutional coup d’état fomented by the prime minister Ngo Dinh Diem, an anti-Buddhist, anti-French, anti-communist, supported by the United States.

Too late. My father had already fallen in love with Vietnam. He was all his life. Every year until the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, he spent several months in South Vietnam. He directed short films, a feature film « Transit in Saigon » in 1962, institutional films, TV reports and documentaries. He had many Vietnamese friends, among them general Tran Van Doan and his brother in law general Le Van Kim who were both among the investigators of the coup d’état which toppled Ngo Dinh Diem and lead to his assassination in 1963. Until the end of his life he remained a Vietnamese at hearth. I also remember a diner he had invited me to with the ex-emperor Bao Dai in a Paris restaurant in the 80s.

When he was coming back from his stays, he always brought present from Vietnam to us. So, as a child, I was wearing Vietnamese pajamas, wooden slippers and I was breathing the perfume of pagoda incense in our Parisian apartment. When his Vietnamese friends were coming for dinner, I remember eating on the floor dishes from Vietnam cooked by my mother. His stories about French Indochina and Vietnam, where he never brought me, have inhabited my childhood.

In 1956, he adapted a Vietnamese legend into a middle length film, the legend of the shadow, giving it the name « The Young Woman of Nam Xuong ». A film quite touching for me who can hear and see its hidden secrets.

It starts with the return of a soldier at his home after four years in the war.

He is going to see his wife at last, and for the first time his son born just after he left. While he is walking on the way through the forest, the first words of the film, pronounced in his head, are: « At home… at home at last… ». My father was at home in Vietnam.

The last sequence crown the happy end of the story by a ceremony of the ancestor’s cult. It ends by a long look from the young woman, powerful and mysterious. A look piercing the camera lens and addressed to, not the director but the man within him.

I have watched this film time and time since my birth. It is years later, after I had children myself, that my father told me about his double life. One in France with our family, the other one in Vietnam with this young woman of Nam Xuong. She became a journalist and wrote books, notably one about the Tibetan struggle. He introduced me to her in Bangkok few years before he died.

So, my links with Vietnam were strong as those with my father. Such as said in the Himalayan proverb: « Earth is your mother, travel is your father ».

He was my best enemy during my teenage years before to become my best friend during a memorable reunion at the Continental Hotel in Saigon in 1974. Our relations merit a book from now on, but let’s keep on the Vietnamese part.

The enemy appeared at the death of my mother when I was 14 years old. I saw my father collapse. Then not able to care of me. A 5 years’ war followed. He was extreme rightist, I became extreme leftist, he was nostalgic of the French colony in Vietnam, I demonstrated against the Vietnam war. « US go home! » I have shouted an incalculable number of time, wishing the communist victory. I ceased forever to call him « dad », instead I named him « fascist » or in the good days by his first name: Jean. My rejection went up to ask for my emancipation in court at the age of 17. He accepted it.

I took the road, starting to discover the world, alone. Even if I refused to admit it, he was always somewhere, sometime in the back ground. There were the cargo ships, the learning of life, and one day this stopover in Saigon where he was himself for a TV documentary. Escaped with long hairs and a revolutionary look, I had now a very short haircut, a face tanned by the sun of a seaman. He did not recognize me when I shouted his first name through the large open cafe space of the Continental hotel, he took me for a G.I. It is in Saigon that we became friends.

Gone again, this time hitchhiking on the road to India the following year, I did not give him any news for four months. But he was present in me when my hearth leaped in Pondicherry learning the fall of Saigon.

Ah, this week in Calcutta! A week of dilemma looking at my money left, with which I could either go back to France or take the plane to Bangkok, then the bus to Vientiane where I would arrive with empty pockets. Finally, I draw lots with an Indian coin of five anas, therefore I still always claim my freedom of choice. Laos won.

(I tell all these stories in the books I have written. They are waiting for an editor.)

We learned to become great friends. When, in the turmoil of the Pathet Lao take over, I proposed to do a documentary on the red prince, future president of the PDRL, he supported the idea.

Then, during these four years when I followed the refugees, we have been together the precursors of information about the boat people, making a documentary, hand in hand, in Singapore and Indonesia, « The Hong Ha and the others… »

It was just before I accompany Gary, just before we crossed our ways with Nam… until we achieve now this loop 38 years later.

We never know all the truth. We discover it bit by bit, at the condition to be able to see. And it is always about who we are really.

Collectively in the history of the world as much as individually in our own history. One cannot be understood without the other.

"The face of this man is not anymore the one appearing on my Facebook account. I have long hair over shaved sides and my body is extensively tattooed."

– Vincent Leduc, Paris, France

January 2016

NEXT

Thirty-four years had passed before Vincent and I connected on Facebook and learned of our crossed paths. Seeing Vincent’s photographs of our journey was a dream-like experience which I will never forget.

In The Same Boat - 1979

SHARE THIS

>> GO TO DESKTOP SITE