My Singapore Misadventure, 1979

In The Same Boat

About Us

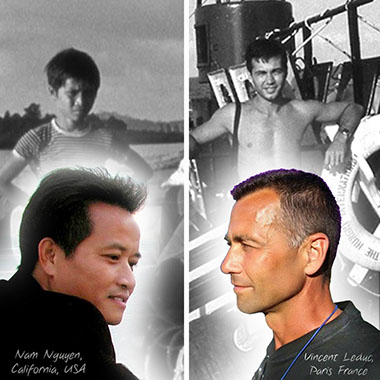

My name is Nam Nguyen. In May, 1979, Vincent Leduc, a young French photojournalist, and I, a runaway Vietnamese teenager, were on the same unsuccessful refugee boat sailing from an overcrowded refugee camp in Indonesia to Singapore, seeking asylum. We were not aware of each other's presence on that small wooden boat until we connected on Facebook 34 years later, in September 2013. After viewing Mr Leduc’s photographs, and recognizing my own face captured in those images, I reached out to him. Mr. Leduc currently lives in Paris, France, and I live in Sacramento, California, U.S.A.

"... I feel so blessed to see these images after all these years. The story never left me. Thanks for working hard to share your incredible photojournalist work with me and others."

Facebook comments, September 2013

"... This is the proof that we never know everything, it is a good lesson for a journalist as well as for any body who believe that he knows something for sure, that he knows the Truth. There is no Truth. Only truth."

Facebook comment, September 2013

ABOUT

Nam Nguyen

I am a former boat refugee from Vietnam. Following a six-month stay at a refugee camp in Indonesia, I arrived in the U.S. in late November 1979. Eight years later, I became a naturalized U.S. citizen. I attended junior high and high school in Nebraska and graduated from University of Nebraska at Kearney in 1989. I’ve spent more than 21 years working at three major newspapers as a graphic journalist and director. I am currently working as a web designer and presentation specialist at an energy engineering and consulting firm located in Sacramento, California.

1975

Until the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, my father was stranded in North Vietnam, separated from his first wife, and their only son for more than 25 years. During that time, he met my mother and started another family. After the Fall of Saigon, my father was able to search for his long lost loved ones. Leaving behind my mother and my three brothers and sister in the North, my father took me on a remarkable 1700 km journey from Hanoi to Saigon. For days my father and I traveled over broken bridges, through bombed roads and cities, and through the countryside of North and Central regions that were littered with battered U.S. military equipment and artillery shells. We walked along with North Vietnamese soldiers and displaced civilians. We hopped between trucks, buses, river ferries, and cow wagons.

When my father finally located his family in the South, he learned that his first wife had become a nationalist, and their son, who was in his late 20s, was a policeman. They were both employed by the formerly U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government. His first wife, whom he hadn’t seen for more than 25 years, no longer accepted him nor wanted anything to do with him. My father was heartbroken. He left me in Saigon to live with my uncle, his youngest brother, a wealthy and respected doctor, while he traveled back to the North to retrieve my mother and my siblings. A year later we were all reunited in the South.

1979

Four years after the last Americans left Saigon (renamed Ho Chi Minh City), the city was in a deep economic crisis. The United States enforced economic embargoes against Vietnam after the end of the war which had taken a heavy toll on the country. The communist government was in full swing targeting the wealthy and the private business owners, taking away big homes and private businesses and using the name of Marxism–Leninism, the socialist ideology that suggested everyone is equal in terms of personal wealth and property. Wealthy citizens were disappearing without a trace, often taken away by soldiers in the middle of the night. Their homes and properties were repossessed by the government. Many home and business owners committed suicide in protest.

Border clashes with China in the North and Cambodia in the Southwest led to fear of another war. There was talk about thousands of people fleeing the country on boats each day. Some of my neighbors and classmates were disappearing randomly and never came back. I heard many terrible stories of people who died at the hands of the police. Those who fled in boats faced starvation, sea storms and pirate attacks as well as the capsizing of their vessels. Still, people were leaving in droves.

The thought of joining the exodus never crossed my mind because it was very expensive, costing approximately 5 to 12 bars of gold per person to escape Vietnam on these boats, and my family was poor. Then one afternoon in early April, my father surprised me with big news: he told me that I could join my cousins to escape my country on a boat. He wanted me to have a better life.

Joining almost a million other Vietnamese fleeing the communist state during the decade after the end of the Vietnam War, I was among 68 people tightly packed in the bottom compartment of a small wooden boat, headed to the Gulf of Thailand in mid April. Pirates attacked our boat repeatedly the second day of our journey. A violent storm came in the late evening just in time to chase the pirates away. The terrifying sea storms continued throughout the night and we were lucky to survive them.

The next morning, pirates continued pursuing our boat. Then a ship appeared from the horizon. About an hour later, all of us on the boat were safely rescued by the “Akuna”. We were on this vessel for about a week before its captain and crews helped us land in a remote island in Indonesia called Buton.

TODAY

Having lived in the United States most of my life, I love my new country dearly for the freedom and all the opportunities that I have had. I feel blessed having a loving family of my own - my wife and our four sons.

I am an artist at heart and I love technology and innovation. I enjoy working with the latest web design and 3D software at my current job. I hope someday to have the time to work on my passion for traditional art: drawing and watercolor painting.

IN RETROSPECT

Starting a new life in a new country with a different language and culture wasn’t easy. It was hard being a teenager without having the unconditional love and support from my parents. Living in the Midwest in the early 80s and being isolated from my family and the Vietnamese culture and community made me feel very homesick and lonely. My artwork helped me through the difficult times. But, those activities did not provide enough of a distraction to help me cope with the sadness and loneliness I felt. During my junior and high school years, I hopped between foster homes and was sometimes admitted to runaway teen shelters when a foster home was not available. These shelters were run very much like a jail – I was locked up, never allowed to leave and the only exposure to the outside was to pull weeds on the property in the heat of the day. I found solace and comfort by keeping myself busy with creating artwork. With my limited English vocabulary, I was not able to express my feelings. But drawing allowed me to release emotions and feelings in a way that other people could understand. It also provided a “bridge” to connect with them. My artwork provided a comfortable topic of conversation when, otherwise, no one would know what to say to the lone Vietnamese boy.

Spiritually speaking, I am still the same person I was the day I left my family and my home country of Vietnam 37 years ago. My heart still holds onto the young boy who was robbed of his innocence by time and circumstance. There is something missing, perhaps lost forever, that can never be recovered. To this day, I still find myself searching for that missing piece.

My immigration document from 1979 stated my birthplace as Saigon, South Vietnam, instead of North Vietnam’s capital city of Hanoi. It was due to my parents’ concern for my safety. I wished I didn’t have to lie about my place of birth to everyone -- my sponsor families from the Holy Cross Lutheran Church, teachers, classmates, friends, coworkers, bosses, neighbors and even my best friends whenever they asked about my family and hometown in Vietnam. It is something I still feel I need to hide in order to protect myself.

I still carry a slight Northern Vietnamese accent today. Living in an English-speaking world most of my life, I no longer think in my native language, but in English. However, my accent still exists and has led to numerous awkward moments with fellow Vietnamese living in the United States. Some turn their heads in my direction and look at me curiously. People often react with confused and skeptical expressions upon hearing I was born in Saigon. Short conversations often end quickly with an inquiry as to the specifics of my Vietnamese origins. I used to wonder if it was because of my lack of Vietnamese vocabulary, or perhaps that I’ve said something inappropriate. I eventually came to the conclusion that my Northern accent was recognizably different than the accent of the South Vietnamese, especially to family members of former U.S. backed South Vietnam military veterans. Many of these people were survivors of Communist Re-Education camps and had formed negative associations with the Northern accent. As a refugee, having this characteristic that I could not change or easily hide made me feel like an outsider and I wished more than ever to be reunited with my family in Vietnam. As an adult, I am still very aware of the assumptions other Vietnamese people make about me when they hear me speak.

I will never forget a special gathering with all of my cousins in Southern California during the late summer of 1989. We were enjoying a wonderful authentic Vietnamese dinner with lively discussion about Vietnamese foods. We were talking about the unique cooking styles and tastes of three regions in Vietnam: Northern, Central and Southern. We debated about which region excelled in the preparation of certain dishes. Then out of the blue, one of my cousins looked at me and asked, “Which region do you identify yourself with? Do you see yourself as a Northerner or Southerner?” I told everyone right away, “I feel that I am both, so I am just a Vietnamese.” Then the same cousin demanded: “You can only pick one, a Northerner or a Southerner?” Everyone was quiet. I paused for a moment and said, “Well, I was born and grew up in the North and I only lived in the South for four years, so I feel more like a Northerner.” My cousin continued, “So you say you are a Northerner?” I nervously reassured, “Yes, I am a Northerner.” The joyous atmosphere evaporated into thin air. The conversation was over. No one was talking as we ate the rest of the meal in silence. I felt hurt and guilty, thinking that I may have disappointed my cousins with my answer.

My cousins and I arrived in the United States from Buton Camp in late November of 1979. We lived together in our first American home, a rental house, in Kearney, Nebraska. The church that sponsored us provided the home, a part-time job for my oldest cousin, food and support. It was an exciting short period of our new life in America. I enjoyed learning English at school and attending church services on weekends, but things soon got rough between me and my cousin. This cousin was vengeful, never really accepting me because I was born in the North and he called me a Viet Cong. He was having a difficult time dealing with a leg wound he suffered in a house fire during the war. I believe due to the pain from not having the medication he needed, his personality became unpredictable and he sometimes turned violent against me.

The fights usually started the moment he saw me come home from school. As soon as our eyes met, the chase began. Books would fly everywhere as I used my backpack to shield myself against my cousin’s kicks and punches. Even when I locked myself in the bathroom for a bath, he kicked down the door and we would wrestle in the bathtub water while I was naked. I usually restrained myself from fighting back, waiting for an opportunity to break free from him so I could run away. On one particular occasion, it was in the middle of a freezing winter in Nebraska so I couldn’t run outside. My cousin chased me all over the house and we ended up wrestling in the living room. During this struggle, we locked each other’s necks to the floor for so long that we both became so tired, unable to move, and almost out of breath. We had many similar fights. One time I ran to our back yard in the dark and freezing snow while wearing only shorts and no socks or shoes, and hid behind a garbage bin for several hours. I also recall a time when I hid in the floor heating duct under the area rug of the family room after being chased by my cousin. I felt bad for my other cousins who were unable to break up our fights, and spent hours searching for me inside and outside of the house so frantically that night. I wanted to let them know where I was hiding, but was afraid the consequences. So, I just stayed calm and slept in that duct all night, not coming out until the next morning.

When all my cousins decided to move away from Kearney to bigger cities in Nebraska and California in the spring of 1980, I took the opportunity to stay behind in Kearney, alone, and began living with foster families. Since then, each of us has moved on with our own lives and become busy with our careers and families. We haven’t seen each other much over the past 37 years. To this day, whenever I think of my cousins, I feel there is a distance between us. It saddens me that our shared refugee experience didn’t bring us closer. We each had to deal with the separation from our home country and integration into our new country in our own individual ways. It was a very emotional and difficult time for us all. I don’t have any hard feelings toward them and I am forever grateful to their father, my uncle, for giving me the boat ticket to freedom and the opportunity for me to get where I am today.

As the years go by, I become more content living independently on my own. That is, without the family I left behind in Vietnam and the cousins I fled with. Of course, I still miss them but yearning for them and the culture I remembered, doesn’t have as strong a hold on me. I feel peaceful as an American citizen. The strange thing is I feel more free when I am surrounded by non-Vietnamese people and speaking in English. I had a great experience in college in Nebraska and I was blessed with a wonderful career at three major newspapers for more than 20 years. But life is full of unexpected incidents, and sometimes, in a split second, memories of my childhood living in Northern Vietnam flood back and catch me off guard.

I remember a long carpool ride 17 years ago on a California freeway to a meeting with my boss, a newspaper editor who was a Japanese-American and a Vietnam War Veteran. We talked about our backgrounds and our common struggles as Asian Americans against negative stereotypes. We were having such a wonderful time sharing our stories about the Japanese and Vietnamese foods and cultures in Sacramento area. Then he asked me what part of South Vietnam that I came from, to which I responded Saigon. He launched into a story about his time in the navy and the U.S. bombing raids over North Vietnam and its capital city, Hanoi, in 1972.

As a U.S. seaman on an aircraft carrier in the Gulf of Tonkin, he and the other navy officers worked non-stop for days and nights, loading weapons onto jet fighters. As he relayed his story, I remember my body became tense as I restrained myself from shaking. My hands were sweating as I listened to him described the details: the constant jet breaking sounds, the scorching heat atop the carrier’s deck, and all the rolling bombs and rockets. At this moment, I couldn’t help but recall the living conditions of my family during this non-stop bombing period. My family and all our neighbors had to hide inside a small, deep, wet, dark and muddy underground bunker just outside of Hanoi 24 hours a day, while the earth was shaking and vibrating constantly from the bomb explosions in the near distance. For many days, we couldn’t go to school. We couldn’t even cook our food because the fire and smoke would make our home a bomb target. It was a surreal experience hearing my boss proudly telling me about his service in Vietnam, while I was awash in memories of the consequences of those bombings.

Time has changed. Technology is changing faster than ever before. Vietnam as a country has changed dramatically, both economically and politically, during the past 30 years. Thanks to the power and speed of social media, people in Vietnam today are connected to all parts of the country and all over the world in real time. For the first time, many people have access to news and world events through their personal mobile devices instead of depending solely on the government-run media. Social media has become an important tool to help the people in Vietnam voice their concerns and protest against government corruption with news, photos, and video clips taken with smartphones, then uploaded and shared instantly online. The Vietnamese can now freely travel all over the country and some travel overseas on jumbo jets to work, attend universities, or visit other countries including the U.S.

Just recently, my wife and I were at a casino in Las Vegas for a short getaway trip. We had a dinner at a very nice restaurant and happened to be seated next to a Vietnamese-American couple from San Jose, California. After the introductions, our conversation turned to laughter, champagne, and cheers. Our group happily talked and toasted drinks non-stop. We had so much fun sharing stories about foods and travel trips back to our home country, etc. The Vietnamese couple was telling us about their fast paced lifestyle: regularly dining at fancy restaurants, staying in nice hotels, and often taking air flights to parties with friends to visit fun destinations such as Las Vegas and Los Angeles. We shared our story too; that we have four kids, my wife and I drove many hours to Las Vegas from Sacramento, and that we slept in the back seat of our car for two nights to save time and money. It was such a fun experience chatting with fellow Vietnamese Americans our own age, with similar experiences. We were really enjoying each other’s company.

Suddenly, the Vietnamese man, who was sitting besides me, put his face close to my left ear, and spoke with a heavy Southern accent, “So, you have a Northern accent. You must be a Northerner heh?” I looked at his eyes and studied his facial expressions. He was a few years older than me. He had a funny, happy face, with a warm smile. I was about to give him the usual quick response but my wife, a Southerner and an Amerasian, stepped in right away on my behalf and said “His mother is from the North, his father is from the South.”

The Vietnamese man looked amused and curious as he responded, “I am a Northerner too, but I don’t speak with a Northern accent. My parents moved to the South in 1954. We are Catholic people.” (Note: After the French left Vietnam in 1954, the country was divided into two sides when the Viet Minh Government under Ho Chi Minh took control of the North. As a result, thousands of North Vietnamese Catholics fled southward out of fear that they would be persecuted by the Communists.)

Under the dimmed spotlight glowing on the man’s face, I could see his sparkling eyes staring at me without a blink, as he waited for me to tell my story about my family. So I did just that. I told him that I was born in Phuc Yen, just north of Hanoi. For the very first time, I told a stranger the name of my real hometown. I told him about my father and my mother, how they met, when I was born, and when I moved to Saigon, and when I escaped from Vietnam.

I held my breath for a moment as I waited for the man’s reaction. But he was calm, with a cool look as if he wanted me to tell him more. I felt a little uneasy as the heat from my blood spread rapidly throughout my body. Suddenly the Vietnamese man smiled and raised his champagne glass toward me for another toast. My wife and the man’s partner quickly joined in with their own glasses. Everyone cheered and then our conversation turned to shared stories about our unforgettable experience as boat people and refugees from more than three decades ago.

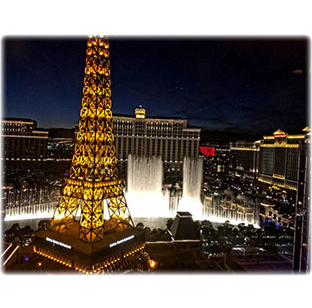

That evening, after returning to our hotel room, I sat alone for several hours enjoying the views through the window of our room on the 24th floor of the Paris Las Vegas Hotel. What a magnificent view of the Eiffel Tower (replica) and the spectacular water show in front of the Bellagio Casino. I felt peaceful and unusually relaxed. I felt the joy of a burden being released. The music wasn’t playing but my heart felt like dancing. I couldn’t stop smiling. Basking in this peaceful state, I took my time, before joining my wife for our usual evening stroll of the Las Vegas Strip. A special feeling still lingers in my soul. I felt extraordinarily powerful. I felt free. Just like a wonderful dream.

That evening, after returning to our hotel room, I sat alone for several hours enjoying the views through the window of our room on the 24th floor of the Paris Las Vegas Hotel. What a magnificent view of the Eiffel Tower (replica) and the spectacular water show in front of the Bellagio Casino. I felt peaceful and unusually relaxed. I felt the joy of a burden being released. The music wasn’t playing but my heart felt like dancing. I couldn’t stop smiling. Basking in this peaceful state, I took my time, before joining my wife for our usual evening stroll of the Las Vegas Strip. A special feeling still lingers in my soul. I felt extraordinarily powerful. I felt free. Just like a wonderful dream.

I dream that someday in the future, I can finally fold these chapters of my life into a book, or other form of communication. Deep inside, I felt the need to share my stories so that I can fully move forward.

Until then, a part of my heart is still in Vietnam.

. . . .

ABOUT

Vincent Leduc

To see the world as a university of life conducted me to travel a lot. Hitchhiking in France and Europe from the age of 15, as a seaman on cargo ships around the world at 19, as a hippie on the road to India at 20, then as a free-lance photographer in South East Asia, where I followed several main subjects: the communist take-over in Laos, the refugee from Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, the consequences of the conflict on Thailand, the Karen and Karenni guerrilla resistances in Burma.

During the last 30 years, I became cameraman, director and producer, founding a production house in Bangkok in 1988. Back to France ten years later, I worked as a travel documentary director for the « Behind the postcard » program which I created, directed and produced for the channel Voyage, then for the « Échappées Belles » program on France 5, for which I have directed numerous « Mythical routes » across the world.

1975

The fall of Saigon on April 30 had the effect of an alert signal on me. I learned the news a month later at the Alliance Française of Pondicherry in India through the newspapers that I came to consult after four month of hippie traveling from France. The Khmer Rouges had taken Phnom Penh on April 17. Only Laos was still reachable. On the road, this country was referred to as the opium paradise, but for me it woke up a powerful feeling for Indochina taking roots from my childhood. It took me about one month to reach it, on June 25, the day after the last Americans were expelled from the country by the communist forces. Far from the horror of the Vietnam war and the atrocities of the Khmer Rouges in Cambodia, the Pathet Lao seized quietly the power in a six-month period during which I had the time to fall in love with the country and decide to live there. Passionate witness of this take over events, I started to take photos on the field, after being officially recognized as a professional photographer by the new authorities thanks to a fake press pass. But two months after the Popular Democratic Republic of Laos proclamation (Dec. 2) I was expelled as most citizens of non-communist countries.

1979

The following four years, I covered the situation of the refugees from Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, from Thailand, with numerous trips to Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. Having just the Mekong river to cross, Laotian and Hmong (mountain people) refugees were the first to arrive, soon reaching by the hundreds of thousand, and were packed into camps all along the border. It took a much longer time for the Khmer to reach such a number. Survivors were arriving sparingly, haggard, terrified, hungry, sick, wounded. Their stories were telling of a state of atrocity we had never known since the discovery of the Nazi concentration camps at the end of World War 2. Bear witness then took another dimension for me.

I started to sell my photos to the international news agency desks, AFP, UPI, AP, in Bangkok. But soon a major problem appeared. There was no demand of news concerning refugees nor any interest for the post-Vietnam war situation. United States were grooming the wound of their first defeat and French as well as American intellectuals, who had supported the communist victory, preferred to keep their eyes, ears and mouth shut. Facing the terrible human drama amplifying rapidly under my own eyes, this incredible and unjust situation committed me to a vocation of observer and witness. These four years were those of silence on the Cambodian genocide taking place in a country turned into a gigantic concentration camp, also silence on the misery of the boat people of whom the precise number were never known. It has been estimated up to 800,000 Vietnamese who succeeded to reach at a cost, with the frightening number of one over two, one who lost his life for one who succeeded.

After three years of this hell, the world suddenly woke up in late 1978 and mostly in mid 1979 when the countries of first temporary asylum in the region threatened to expel all refugees, precisely to alert the world public opinions. It is then, that international medias started to play drum, and launched large mobilization, that people of good will appeared. And Gary landed one morning in Bangkok. I meet him the very evening in a Patpong bar, the famous city red light district. He was drinking a beer next to me at the counter. In an unknown region to him, he needed a guide to go and see the various Food for the Hungry programs, including rescue with the Akuna ship in the South China Sea. It was for me the occasion to bear witness even closer to the boat people.

TODAY

All along my life in the field of picture, I experienced an uncertain equilibrium between the commitment to bear witness, critically, with in depth analysis, and the necessity of works providing a living such as company profile videos, television programs and even commercials. The question of ethics has always been and will always be central to me. At the ultra-liberalism era where everything is allowed, my last experience with this travel program on France 5, drove me to break.

Flirting with writing, pottery and philosophy, I am now living in my garden that I cultivate in a natural way, uniting works of earth, spiritual life, artistic creation and therapeutic curing.

IN RETROSPECT

I was writing a book about my first years of experience as free-lance photographer in South East Asia when I made this search on the Akuna and went across Nam. Among our exchanges one day, he wrote:

« Looking back, I learned that Vincent and I have traveled a very similar time table, and both of our lives have been profoundly affected by the Vietnamese boat people crisis and related events following the end of the Vietnam War. »

Similar calendar?

This affirmation seemed a bit strange to me. Later, I heard he echo. The echo of all those who new me and along my life reacted to my Asian experiences saying: « Ah, you followed the path of your father! » To which I always answered « no » in order to affirm my independence as well as to claim my own choices. The link of all that? Vietnam.

It is a long story.

My father was a film director, graduated from Idhec, the renowned Institute of high cinematographic studies. In 1955, less than a year after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu ending more than a century of French colony, the new South Vietnamese government, Francophile, placed an ad at the prestigious Idhec. It was looking for a director to create a South-Vietnamese cinematography within the cultural and information ministry. My father left with a one year contract the very year of my birth.

He directed his first Vietnamese films in the turmoil of events of that time, especially « North Wind, South Wind », a film shot in 35mm on the exodus of the catholic refugees from North Vietnam, and « Xuan, the Little Buffalo Keeper », telling the story of a peasant boy dreaming to navigate.

The contract broke up before end by the institutional coup d’état fomented by the prime minister Ngo Dinh Diem, an anti-Buddhist, anti-French, anti-communist, supported by the United States.

Too late. My father had already fallen in love with Vietnam. He was all his life. Every year until the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, he spent several months in South Vietnam. He directed short films, a feature film « Transit in Saigon » in 1962, institutional films, TV reports and documentaries. He had many Vietnamese friends, among them general Tran Van Doan and his brother in law general Le Van Kim who were both among the investigators of the coup d’état which toppled Ngo Dinh Diem and lead to his assassination in 1963. Until the end of his life he remained a Vietnamese at hearth. I also remember a diner he had invited me to with the ex-emperor Bao Dai in a Paris restaurant in the 80s.

When he was coming back from his stays, he always brought present from Vietnam to us. So, as a child, I was wearing Vietnamese pajamas, wooden slippers and I was breathing the perfume of pagoda incense in our Parisian apartment. When his Vietnamese friends were coming for dinner, I remember eating on the floor dishes from Vietnam cooked by my mother. His stories about French Indochina and Vietnam, where he never brought me, have inhabited my childhood.

In 1956, he adapted a Vietnamese legend into a middle length film, the legend of the shadow, giving it the name « The Young Woman of Nam Xuong ». A film quite touching for me who can hear and see its hidden secrets.

It starts with the return of a soldier at his home after four years in the war.

He is going to see his wife at last, and for the first time his son born just after he left. While he is walking on the way through the forest, the first words of the film, pronounced in his head, are: « At home… at home at last… ». My father was at home in Vietnam.

The last sequence crown the happy end of the story by a ceremony of the ancestor’s cult. It ends by a long look from the young woman, powerful and mysterious. A look piercing the camera lens and addressed to, not the director but the man within him.

I have watched this film time and time since my birth. It is years later, after I had children myself, that my father told me about his double life. One in France with our family, the other one in Vietnam with this young woman of Nam Xuong. She became a journalist and wrote books, notably one about the Tibetan struggle. He introduced me to her in Bangkok few years before he died.

So, my links with Vietnam were strong as those with my father. Such as said in the Himalayan proverb: « Earth is your mother, travel is your father ».

He was my best enemy during my teenage years before to become my best friend during a memorable reunion at the Continental Hotel in Saigon in 1974. Our relations merit a book from now on, but let’s keep on the Vietnamese part.

The enemy appeared at the death of my mother when I was 14 years old. I saw my father collapse. Then not able to care of me. A 5 years’ war followed. He was extreme rightist, I became extreme leftist, he was nostalgic of the French colony in Vietnam, I demonstrated against the Vietnam war. « US go home! » I have shouted an incalculable number of time, wishing the communist victory. I ceased forever to call him « dad », instead I named him « fascist » or in the good days by his first name: Jean. My rejection went up to ask for my emancipation in court at the age of 17. He accepted it.

I took the road, starting to discover the world, alone. Even if I refused to admit it, he was always somewhere, sometime in the back ground. There were the cargo ships, the learning of life, and one day this stopover in Saigon where he was himself for a TV documentary. Escaped with long hairs and a revolutionary look, I had now a very short haircut, a face tanned by the sun of a seaman. He did not recognize me when I shouted his first name through the large open cafe space of the Continental hotel, he took me for a G.I. It is in Saigon that we became friends.

Gone again, this time hitchhiking on the road to India the following year, I did not give him any news for four months. But he was present in me when my hearth leaped in Pondicherry learning the fall of Saigon.

Ah, this week in Calcutta! A week of dilemma looking at my money left, with which I could either go back to France or take the plane to Bangkok, then the bus to Vientiane where I would arrive with empty pockets. Finally, I draw lots with an Indian coin of five anas, therefore I still always claim my freedom of choice. Laos won.

(I tell all these stories in the books I have written. They are waiting for an editor.)

We learned to become great friends. When, in the turmoil of the Pathet Lao take over, I proposed to do a documentary on the red prince, future president of the PDRL, he supported the idea.

Then, during these four years when I followed the refugees, we have been together the precursors of information about the boat people, making a documentary, hand in hand, in Singapore and Indonesia, « The Hong Ha and the others… »

It was just before I accompany Gary, just before we crossed our ways with Nam… until we achieve now this loop 38 years later.

We never know all the truth. We discover it bit by bit, at the condition to be able to see. And it is always about who we are really.

Collectively in the history of the world as much as individually in our own history. One cannot be understood without the other.

"The face of this man is not anymore the one appearing on my Facebook account. I have long hair over shaved sides and my body is extensively tattooed."

– Vincent Leduc, Paris, France

January 2016

NEXT

A New Dream

Learning that Vincent was in the same boat with me on this unforgettable misadventure in the South China Sea during those dark days 38 years ago was miraculous. Seeing his photographs documenting our journey and experiencing it all over again was equally miraculous. This connection has helped me bring closure to my “Runaway to Singapore” story. Well, almost.

SHARE THIS

>> GO TO DESKTOP SITE